Forming a Peace Establishment: Building an Army

After serving 23 years in the National Guard, I noticed a question frequently popping up on our social media pages when we posted about the Kentucky National Guard (KYNG) deploying overseas: Why is the National Guard being federally mobilized and not staying in the U.S. for national defense?

Most would assume the purpose of the National Guard was established only for state-side national defense.

The debate about National Guard units remains highly debated in different states’ legislatures, including Kentucky, with the 25 Regular Season House Bill 141, an ACT relating to the Kentucky National Guard.

Militia forces, the predecessors to the National Guard, existed prior to the colonies declaring independence. Specifically, on December 13, 1636, the Massachusetts Bay Colony General Court formed a militia of citizens to protect the early colony prior to the unionization of the territories, making it older than the federal army.1

Figure 1. The First Muster by Don Trojani, courtesy of the National Guard Bureau.

Figure 1. The First Muster by Don Trojani, courtesy of the National Guard Bureau.

This is older than the Regular Army’s birthday, June 14, 1775. One solid explanation of this comes from the fact that early settlers prioritized civilian control of the military. For example, as stated in the Constitution, the president is the commander-in-chief of the military in times of war.

These are the same ideals that underpin all legitimate defense organizations, which are formed through elected representatives.

In the case of Kentucky, the KYNG celebrates their birthday on June 24 every year, even though the actual act, titled “An Act to Arrange the Militia of this State into Divisions, Brigades, Regiments, Battalions and Companies, and for other purposes.”, was signed into law by Gov. Isaac Shelby on June 24, 1792.

Figure 2. Kentucky General Assembly. "Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky." Frankfort, Legislative Research Commission (1792): 37.

Figure 2. Kentucky General Assembly. "Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky." Frankfort, Legislative Research Commission (1792): 37.

During and after the Revolution, Americans had two prevailing thoughts on a standing military. One side supported a large standing army while the other supported citizen-soldier armies belonging to the colonies.

During the formation of the Constitution, the argument for a large standing army of regular forces was introduced by soon-to-be Federalists such as Alexander Hamilton, with the support of General George Washington. The logic was for a well-trained force that could be readily available to defend the nation almost immediately.

The Anti-Federalists, Thomas Jefferson and John Hancock, wanted the states to have more power and be responsible for national defense. They believed a force of citizen-soldiers was less likely to form together to overthrow the young government they were trying to create.

Washington witnessed the problems with having two different types of armies and identified them during the Revolution. While local militias were able to defend themselves well, their integration with the new Regular Army was problematic due to a lack of common standards in fighting in formation, uniforms, weaponry, and funding.

Washington wrote the “Sentiments on a Peace Establishment” to craft a standard plan for all militaries of the new nation.2

First, a regular and standing force to run the garrisons and outposts, protect trade, prevent encroachment, and guard from surprise attacks. Second, a well-organized militia that would be modeled after the Regular Army. Third, a series of arsenals and depots to store munitions and weapons. And finally, military academies for initial enlistees, officer training, and advanced training for army engineers and artillery.

After a long debate, the Second Continental Congress created the first standing force, the Continental Army, on June 14, 1775—the birthday of the Continental Army or the U.S. Army.

After the Revolution, the Anti-Federalists passed an amendment into the Bill of Rights to give the states the ability to raise militias unimpeded.

Federalists saw this as a net-positive for them to use as a “reserve force” for the Regular Army. If the states were to have their own militias, then Congress could federalize those forces and have control over a larger fighting force. However, Congress and the states found that the cost of standardizing a much larger part-time force would be higher—$400,000 annually—than they were willing to pay.3

In May of 1792, Congress’s solution was the Militia Act of 1792, which required all able-bodied men to enroll in their state’s militia and provide their own weapons. No federal money would go towards the states’ militias and each governor would appoint an adjutant general to commission officers of each regiment and brigade, staff, and provide reports to the federal government on manning, equipment, and readiness.

Throughout the nineteenth century, including the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War, it became increasingly obvious that this model was not working. Four main reasons explain the struggles of the militia model:

First, Congress wanted the militiamen to supplement the Regular Army with individuals and not units. However, militiamen wanted to mobilize as units; they were community-based organizations that included family members and neighbors. There was both a sense of familiarity and esprit-de-corps within the militias that gave trust in each other and the officers under whom they served.

Second, there was a lack of adequate training and time. Militias were not well-funded, and the state's weapons were often rejects or relics from the federal army.

One such example is a three-pounder “Burgoyne Cannon” that was first captured by American forces during the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 and later given to Gov. Isaac Shelby.

Time was also a large factor, as muster days were held only once or twice a month, with occasional summer camps. Within that short timeframe, Congress expected them to train to the same standard as the regular force.

Third, state militias were under the command of their governors. Like today, they were often called upon to assist local law enforcement and emergency services in response to natural disasters and civil unrest.

Fourth, militia officers did not meet federal standards. The requirements for being commissioned were different by appointment rather than training and merit. A dearth of military education was also a major concern.

And finally, to be as blunt as possible, officers of the militia were physically unfit for leadership positions expected of an officer. One of the primary reasons was due to their age. The lead from the front mentality of the regulars could not be accomplished by the commissioned and noncommissioned officers of the militia.4

These concerns ultimately led to three acts that transferred states’ militias into the National Guard the United States knows today.

Standardization began with the Militia Act of 1903, named after Senator Charles Dick, previously a Major General in the Ohio National Guard. He was also the president of the National Guard Association of the United States, a group of members and alumni of militia members who officially lobby for benefits and laws pertaining to states’ militias.

States’ soldiers, by United States law, must drill twenty-four times a year, at least one night every two weeks, and troops must attend a one-week summer camp. All training would adhere to the Regular Army’s regulations and performance standards.

To incentivize this, states that complied with those standards would receive a $2 million subsidy in federal dollars.

In 1908, to increase compliance, the incentive was raised to $4 million, and the militias would have representation in the War Department by the Division of Militia Affairs.

With recommendations by Major General Leonard Wood, Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916. This act formally gave the United States a true reserve force in times of national defense, but gave more federal control over this new group of citizen-soldier formations, now known as the National Guard.

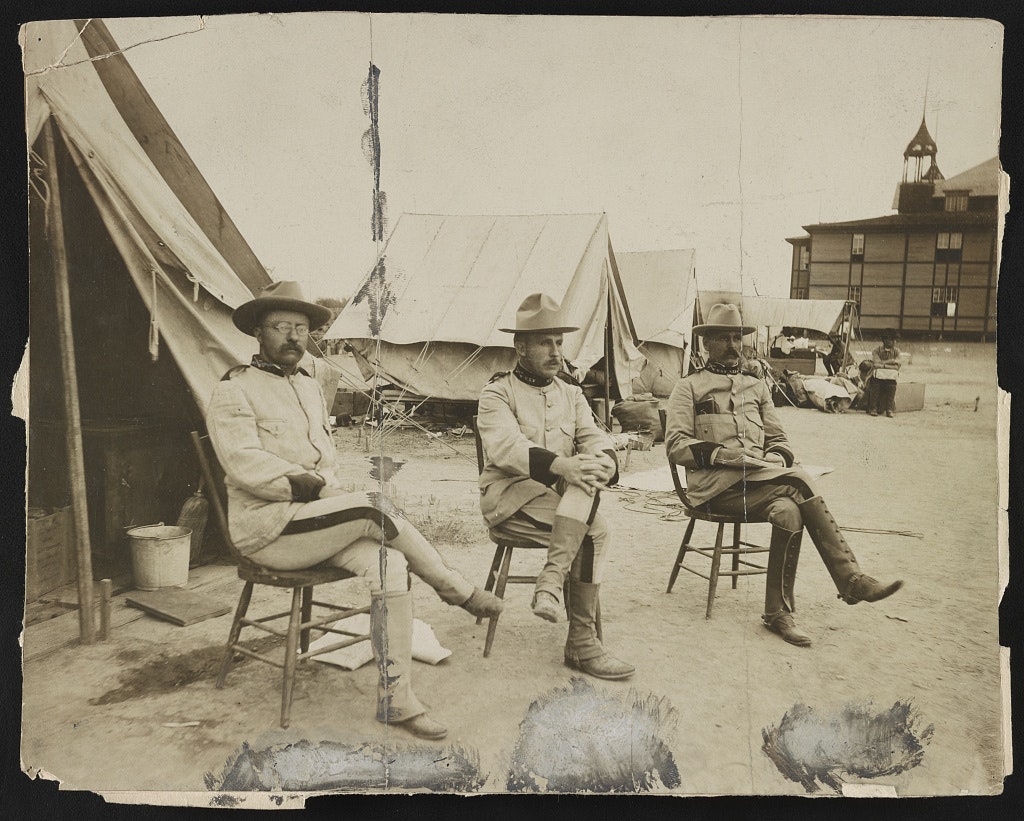

Figure 3. Future-President Theodore Roosevelt, left, Army Capt. Leonard Wood, center, and Army Maj. Alexander Brodie rest at a military camp in San Antonio. Library of Congress. 1898.

Figure 3. Future-President Theodore Roosevelt, left, Army Capt. Leonard Wood, center, and Army Maj. Alexander Brodie rest at a military camp in San Antonio. Library of Congress. 1898.

Drill days are increased to forty-eight days, and soldiers would take a dual oath: one to their state’s constitution and one to the defense of the national constitution.

For soldiers in the National Guard, there became a major incentive to join; the federal government would provide pay and benefits to the soldiers when they attended training.

The NDA of 1916 supported states to receive federal funding for the military, incentivized a true, all-volunteer army, and increased manpower in the army by twofold.

This included changing the naming convention of the states’ militaries to the federal naming convention, such as changing the 3rd Company, 113th Ammo Train to the 113th Ordnance Company in the Kentucky National Guard.

As of March 2025, according to the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC), there are 385,252 members in the Regular Army and 313,857 serving as a reserve force in the National Guard.5

And after over 250 years of the debates between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, we are seeing the results of Washington’s sentiments on his plans for an effective army.

For questions or comments on this article, please contact Andy Dickson at andrew.dickson@ky.gov.

___________________________________

- National Guard Bureau, I Am the Guard: A History of the Army National Guard, 1636-2000, (National Guard Bureau: 2001), 25.

- Washington, George, Washington’s Sentiments on a Peace Establishment, 1 May 1783, (National Archives).

- National Guard Bureau, I Am the Guard, 68.

- Allan R. Millet, “The Constitution and the Citizen-Soldier,” in Papers on the Constitution, ed. John W. Elsburg (Center of Military History, 1990), 106-107.

- Defense Manpower Data Center, Number of Military and DoD Appropriated Fund Civilian Personnel, accessed July 22, 2025.